- Trio of CRISPR Discoverers Awarded a $1 Million Kavli Prize

- CRISPR Therapeutics, a Startup Company, Will Soon Start Clinical Trials

- New Issue: Concerns for Cancer

Over the past few years, I have periodically blogged about CRISPR-based gene editing, which has been arguably the hottest trending topic in nucleic acid-targeted therapy for about the past five years or so. The catalyst for this burst of publications was a 2012 report in Science on a study led by Doudna and Charpentier (see below). The study focused on the potential utility of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome editing, and it currently has over 5000 citations in Google Scholar. There are ~7400 articles in PubMed indexed to CRISPR, and it is evident from my chart shown here that there is strong growth in the annual number of CRISPR publications in the PubMed database.

Number of CRISPR publications in PubMed

Number of CRISPR publications in PubMed

In May 2018, three pioneers in CRISPR technology—Emmanuelle Charpentier of the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in Berlin, Virginijus Šikšnys (see Footnote) of Vilnius University in Lithuania, and Jennifer Doudna of the University of California, Berkeley—were awarded the $1 million Kavli Prize in Nanomedicine. This highly prestigious prize from The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters was awarded “for the invention of CRISPR-Cas9, a precise nanotool for editing DNA, causing a revolution in biology, agriculture, and medicine.”

Emmanuelle Charpentier, Virginijus Šikšnys and Jennifer Doudna (left to right). Taken from quantamagazine.org

Emmanuelle Charpentier, Virginijus Šikšnys and Jennifer Doudna (left to right). Taken from quantamagazine.org

As far as invention goes, there has been continued litigation, recently summarized in a GEN interview with law professor Jacob Sherkow titled CRISPR in the Courthouse. The University of California, Berkeley (UC) and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard are at odds over foundational patents covering CRISPR-Cas9. Interested readers should consult “late breaking news,” which covers the recent issuance of a US patent to UC and its partners.

Notwithstanding unresolved intellectual property matters, so-called “surrogate companies” for the holders of these key patents include Editas Medicine (MIT/Harvard), Caribou Biosciences/Intellia Therapeutics (UC and University of Vienna), and CRISPR Therapeutics (Emmanuelle Charpentier), the latter of which is the focus of the present blog. As you’ll read below, CRISPR Therapeutics is developing a “CTX001” approach for the treatment of Sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia for clinical trials this year, which is a highly anticipated milestone—both scientifically and commercially.

CRISPR Therapeutics CTX001

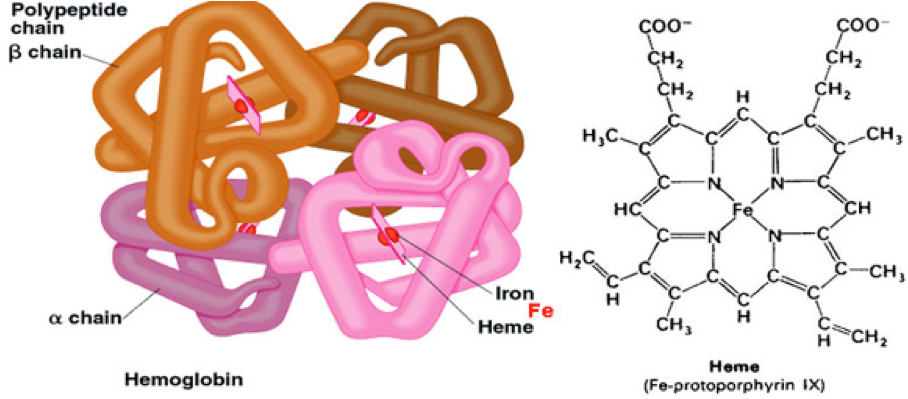

Sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia are caused by genetic mutations in the β-globin gene, which codes for the β subunit of hemoglobin that, as depicted below, is the oxygen carrying component of red blood cells. In these diseases, hemoglobin is missing or defective, which results in devastating medical problems. The approach developed by CRISPR Therapeutics is designed to mimic the presence of fetal hemoglobin (HbF; aka γ-globin) that is present in newborn babies. HbF is a form of hemoglobin that is quickly replaced by adult hemoglobin. However, in rare cases where HbF persists in adults, it provides a protective effect for those who have Sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia.

Taken from socratic.org

Taken from socratic.org

CTX001 is an ex vivo therapy in which autologous (i.e. self-donated) cells are harvested directly from the patient. CRISPR Therapeutics then applies its gene-editing technology to the cells outside of the body, making a single genetic change designed to increase HbF levels in a patient’s own blood cells. The edited cells are then reinfused and are expected to produce red blood cells that contain HbF in the patient’s body, thus overcoming the hemoglobin deficiencies caused by these diseases.

The gene-editing mechanism for CTX001 presented by CRISPR Therapeutics at the American Society of Hematology (ASH) in December 2017 is depicted below. In researching this CRISPR-based mechanism, I found a publication by Bjurström et al. that helps to better understand this depiction. In brief, the zinc-finger transcriptional factor BCL11A has been shown to silence HbF genes in human cells during development, and thus directly regulates HbF switching.

BCL11A silences HbF by associating with other known γ-globin transcriptional repressors. The gene binds to the locus control region as well as other intergenic sites, which prevents the interaction between the locus control region and the HbF globin gene required for fetal globin expression. Using a guide RNA and Cas9 to enable permanent site-specific genome engineering through a DNA repair pathway, knockdown of the BCL11A gene can be an effective strategy for reactivating HbF and restoring functional erythrocytes.

The aforementioned ASH presentation by CRISPR Therapeutics also includes an overview of Sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia, as shown here. According to an informative historical article that I found, Sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia are related genetic disorders that can cause fatigue, jaundice, and episodes of pain ranging from mild to very severe. They are inherited, and usually both parents must pass on an abnormal gene in order for a child to have the disease. Much more genetic information on these two disorders is available on the NIH Genetics Home Reference.

CRISPR Therapeutics Clinical Studies Status

The December 2017 ASH presentation by CRISPR Therapeutics received widespread media coverage that heralded the highly anticipated “bench-to-bedside” transition for CRISPR technology. CTX001 was able to efficiently edit the target gene in more than 90 percent of hematopoietic stem cells to achieve about 40 percent of HbF production, which investigators believe is sufficient to improve a patient’s symptoms. Study results also showed that CTX001 affects only cells at the target site and that it has no off-target effects on hematopoietic stem cells, thereby appearing to be a safe potential treatment.

These positive results prompted CRISPR Therapeutics to start a collaboration with Vertex Pharmaceuticals to develop and commercialize CTX001 treatment of Sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. It was also announced that CRISPR Therapeutics and Vertex are planning to submit an investigational new drug (IND) application to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to start a Phase 1/2 clinical trial in Sickle cell disease in the United States in 2018. In addition, CRISPR Therapeutics also submitted a clinical trial application (CTA) for CTX001 to advance into a Phase 1/2 clinical trial in patients with β-thalassemia in Europe in 2018. This trial will evaluate the safety and effectiveness of CTX001 in adult patients with transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia.

After the above announcement, News Atlas reported that the FDA placed a clinical hold on this Phase1/2 trial of CTX001 pending, according to CRISPR Therapeutics, ‘the resolution of certain questions that will be provided by the FDA as part of its review of the IND.’

Concerns for Cancer

In studies published in June 2018 in venerable Nature Medicine, researchers from Sweden’s Karolinska Institute and, separately, Novartis, found that cells whose genomes are successfully edited by CRISPR-Cas9 have the potential to seed tumors inside a patient. CRISPR-Cas9 works by cutting both strands of the DNA double helix. That “injury” causes a cell to activate a gene called p53, which has been called the “Guardian Angel of the Genome” and is the most studied of all human genes, which you can read about in one of my previous blogs.

Whichever action p53 takes, the consequence is the same: CRISPR doesn’t work as intended because the genome edit is mended, or the cell dies. The flip-side of p53 repairing CRISPR edits, or killing cells that accept the edits, is that cells that survive with the edits do so because they have a dysfunctional p53. The reason why that could be a problem is that p53 dysfunction can cause cancer. The p53 gene is reported to be the most frequently mutated gene in human cancer: about 50% of all human cancers have lost p53 or express an inactive, mutant p53.

As a result, the Novartis paper concludes that “it will be critical to ensure that [genome-edited cells>

have a functional p53 before and after [genome>

engineering.” The Karolinska team warns that p53 and related genes “should be monitored when developing cell-based therapies utilizing CRISPR-Cas9.”

An article in statnews.com quotes the CEO of CRISPR Therapeutics, Sam Kulkarni, as saying that these p53 findings are “something we need to pay attention to, especially as CRISPR expands to more diseases. We need to do the work and make sure edited cells returned to patients don’t become cancerous.”

Closing Comments

Many years ago, I was among the early investigators of antisense therapeutics, which at the time was viewed as a new paradigm that would enable faster bench-to bedside, compared to traditional small molecule drug development. In reality, the antisense approach encountered unforeseen complications and required ~30 years of development to reach demonstrable clinical utility, which I previously wrote about in another blog. Short-interfering RNA (siRNA)-based therapeutics also encountered similar struggles.

While past history is not a predictor of the future, in my humble opinion, CRISPR-based clinical strategies will continue to have to deal with unexpected issues, such as the above p53 situation. While I remain hopefully optimistic about future clinical successes for CRISPR, I won’t be surprised if some of these achievements come slower than currently anticipated.

As usual, your comments are welcomed.

Footnote

According to June 8, 2018 Science News at a Glance, Virginijus Šikšnys, whose role in the invention of the revolutionary genome editor CRISPR has often been overlooked, received some vindication when he was named a co-winner of the prestigious Kavli Prize in Nanoscience. Šikšnys will share the $1 million award with Doudna and Charpentier, who have received far more attention. Šikšnys first showed that the CRISPR system could be transferred from one bacterium to another. And like Doudna and Charpentier, he independently designed a way to steer the CRISPR complex to specific targets on a genome, which he called “directed DNA surgery.”