- Clinical Alert for Candida auris (C. auris) Issued by CDC

- US Concerned About C. auris Misidentification and Drug Resistance

- Sequencing C. auris DNA in Clinical Samples is Preferred for Identification

Strain of C. auris cultured in a petri dish at CDC. Credit Shawn Lockhart, CDC. Taken from foxnews.com

Strain of C. auris cultured in a petri dish at CDC. Credit Shawn Lockhart, CDC. Taken from foxnews.com

When I was a kid and didn’t know better, there was a supposedly funny rhyme that “there’s fungus among us.” While this saying is thankfully passé nowadays, the growing number of infections by a formerly obscure but deadly fungus is frightening. This so-called “superbug” is an antibiotic-resistant fungus called Candida auris (C. auris) that’s worth knowing about, and is the fungal focus of this blog.

First, Some Fungus Facts

Fungi are so distinct from plants and animals that they were allotted a biological 'kingdom' of their own in classification of life on earth, although that was only relatively recently, i.e. 1969. There are 99,000 know fungi, which exist in a wide diversity of sizes, shapes and complexity that extends from relatively simple unicellular microorganisms, such as yeasts and molds, to much more complex multicellular fungi, such as mushrooms and truffles.

It was previously thought that genomes of all fungi are derived from the genome of the model fungus Saccharomyces cerevisae, which has been used in winemaking, baking and brewing since ancient times. However, genome sequencing of more than 170 fungal species has revealed that, while the genome size of S. cerevisae is only ~12 Mb, seven species of fungus have genome sizes larger than 100 Mb. This is attributed to various evolutionary pressure-factors generating transposable elements, short sequence repeats, microsatellites, and genome duplication, and noncoding DNA.

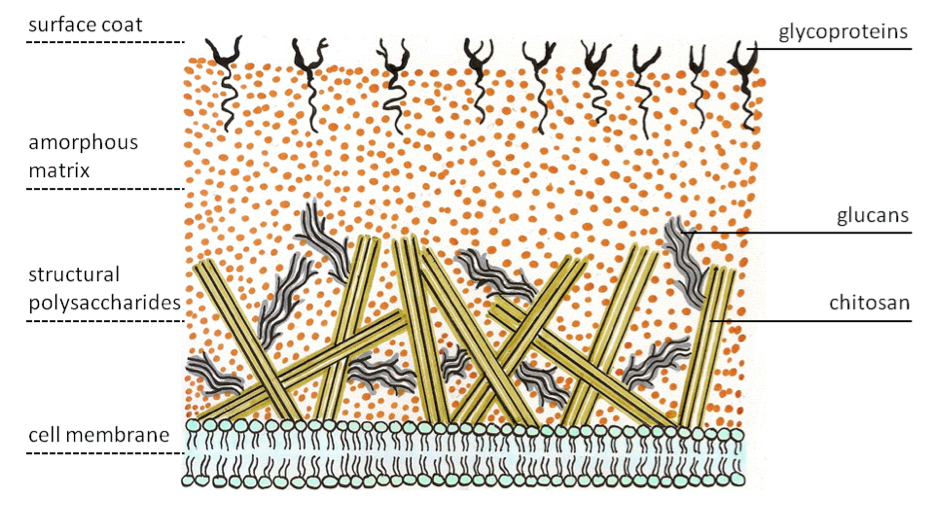

Fungal cell walls are made up of intertwined fibers mostly comprised of long chains of chitosan, the same tough compound found in the exoskeletons of animals such as spiders, beetles and lobsters. The chitin in fungal cells is entangled with glucans and other wall components, such as proteins, forming a mass that protects the cell membrane behind it—and posing a formidable barrier against antifungal drugs.

Taken from Wikipedia.org

Taken from Wikipedia.org

In researching whether there are any nucleic acid drugs against fungi, I found one early patent by Isis (now Ionis) Pharmaceuticals for use of antisense phosphorothioate-modified oligonucleotides for the treatment of Candida infections, but virtually no other reports. I suspect that will change in the future as pathogenic fungi and other disease-causing microbes become more resistant to conventional drugs.

Fungal infections of the skin are very common and include athlete's foot, jock itch, ringworm, and yeast infections. While these can usually be readily treated, infections caused by pathogenic fungi have reportedly risen drastically over the past few decades. Moreover, with the increase in the number of immunocompromised (burn, organ transplant, chemotherapy, HIV) patients, fungal infections have led to alarming mortality rates due to ever increasing phenomenon of multidrug resistance.

Segue to a Serious Situation

Emergence of drug-resistant fungi is, in part, the segue to the serious story of the present blog. The other part being incorrect identification of a certain fungus as being a common candida yeast, which is not only scary but seemingly inexcusable in today’s era of highly accurate PCR-based assays to accurately identify microorganisms. Here’s the situation in a nutshell.

- auris infection, which is associated with high mortality and is often resistant to multiple antifungal drugs, was first described in 2009 in Japan but has since been reported in countries throughout the world. Unlike many Candida infections, C auris is a hospital-acquired infection that is contracted from the environment or staff of a healthcare facility, and it can spread very quickly.

To determine whether C. auris is present in the United States and to prepare for the possibility of transmission, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention issued a clinical alert in June 2016 requesting that C. auris cases be reported.

(A) MALDI-TOF schematic; (B) mass spectra from three C. parapsilosis; and (C) two C. bracarensis isolates. Taken from researchgate

(A) MALDI-TOF schematic; (B) mass spectra from three C. parapsilosis; and (C) two C. bracarensis isolates. Taken from researchgate

This official alarm bell, if you will, was triggered by the following facts:

- Many isolates are resistant to all three major classes of antifungal medications, a feature not found in other clinically relevant Candida

- auris identification requires specialized methods such as a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry or sequencing the 28s ribosomal DNA, as pictured below.

- Using common methods, auris is often misidentified as other yeasts, which could lead to inappropriate treatments.

The CDC subsequently found that seven cases were identified in Illinois, Maryland, New York and New Jersey. Five of seven isolates were either misidentified initially as C. haemulonii or not identified beyond being Candida. Five of seven isolates were resistant to fluconazole; one of these isolates was resistant to amphotericin B, and another isolate was resistant to echinocandins. While no isolate was resistant to all three classes of antifungal medications, emergence of a new strain of C. auris that is would pose a serious public health issue.

Based on currently available information, the CDC concluded that these cases of C. auris were acquired in the U.S., and several findings suggest that transmission occurred:

- First, whole-genome sequencing results demonstrate that isolates from patients admitted to the same hospital in New Jersey were nearly identical, as were isolates from patients admitted to the same Illinois hospital.

- Second, patients were colonized with auris on their skin and other body sites weeks to months after their initial infection, which could present opportunities for contamination of the health care environment.

- Third, auris was isolated from samples taken from multiple surfaces in one patient’s health care environment, which further suggests that spread within health care settings is possible.

A related Fox News story adds that C. auris was found on a patient’s mattress, bedside table, bed rail, chair, and windowsill. Yikes!

While the above situation in the U.S. might not seem particularly worrisome to you, the potential for emergence of more infectious C. auris strains with higher lethality should be of concern. That has already reportedly occurred in several Asian countries and South Africa. Obviously, deployment of the best available methods for pathogen identification can, in principle, lessen the likelihood of the emergence and/or spread of C. auris in the U.S. and other countries.

Case for Point-of-Care C. auris Nanopore Sequencing?

Regular readers of my previous blogs know that I’m an enthusiastic fan of the Oxford Nanopore Technologies minION sequencer, which is proving to be quite useful for characterizing pathogens in very remote regions on Earth—and even on the International Space Station to diagnose astronaut infections! Notwithstanding various current limitations for minION sequencing of microbes, it seems to me that it would be relatively straightforward to generate minION data for many available samples of pathogenic fungi and genetically related microbes to assess the feasibility using minION for faster, cheaper, better unambiguous identification of C. auris minION in centralized or Point-of-Care applications.

If you think this suggestion is farfetched, think again, after checking out these 2016 publications using minION:

The 51.4-Mb genome sequence of Calonectria pseudonaviculata for fungal plant pathogen diagnosis was obtain using minION.

The first report of the ~54 Mb eukaryotic genome sequence of Rhizoctonia solani, an important pathogenic fungal species of maize, was derived using minION.

Sequence data is generated in ~3.5 hours, and bacteria, viruses and fungi present in the sample of marijuana are classified to subspecies and strain level in a quantitative manner, without prior knowledge of the sample composition.

CDC on C. auris Status and FAQs

In the interest of concluding this blog with the most up-to-date and authoritative information, I consulted the CDC website and found statements and replies to FAQs that are well worth reading at this link.

As a scientist, my overriding question concerns the lack of adoption of improved microbiological methods by hospitals and clinics. The above noted misidentifications of C. auris infections resulting from use of flawed lab analyses seems unacceptable. Although I don’t know all the facts or statistics to generalize, I suspect that there are other incorrect lab analyses due to use of outdated methods. On the other hand, I’m hopeful that, with the FDA’s widely touted Strategic Plan for Moving Regulatory Science into the 21st Century, the section entitled Ensure FDA Readiness to Evaluate Innovative Emerging Technologies—think nanopore sequencing—becomes actionable, sooner rather than later.

Changing established—dare I say entrenched—clinical lab tests is not simple or easy, but if it doesn’t begin it won’t happen, about which I’m quite certain. I can only wonder why development of infectious disease analytical methods and treatments seem to require a crisis. Sadly, I think it boils down to the complexities and socio-political dynamics of who pays.

Frankly, it’s my personal opinion that maybe it’s time Thomas Jefferson’s philosophy about hammering guns into plows is directed to health care.

Postscript

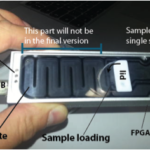

After writing this blog, I learned that T2 Biosystems has received FDA approval to market in the U.S. the first direct blood test for detection of five yeast pathogens that cause bloodstream infections: Candida albicans and/or Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, Candida glabrata and/or Candida krusei.

Yeast bloodstream infections are a type of fungal infection that can lead to severe complications and even death if not treated rapidly. Traditional methods of detecting yeast pathogens in the bloodstream can require up to six days, and even more time to identify the specific type of yeast present. The T2Candida Panel and T2Dx Instrument (T2Candida) can identify these five common yeast pathogens from a single blood specimen within 3-5 hours.

T2Candida incorporates technologies that break the yeast cells apart, releasing the DNA for PCR amplification for detection by greatly simplified, miniaturized nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) technology, as can be seen in this video.

In my opinion, this fascinating new technology is another example of what could be rapidly deployed toward detecting C. auris.