- Sequencing for Diagnosis of Autism Holds Promise

- Several Genetic-Risk Testing Procedures are Available

- More Than 40 Autism Publications Using TriLink Products

The first National Autism Awareness Month was declared by the Autism Society in April 1970 with the aim of educating the public about autism. Autism is a complex mental condition and developmental disability, characterized by difficulties in the way a person communicates and interacts with other people. Autism can be present from birth or form during early childhood, typically within the first three years. Autism is a lifelong developmental disability with no single known cause.

The puzzle pattern of this ribbon reflects the complexity of autism, while the colors and shapes represent the diversity of people and families living with this spectrum of disorders. Taken from drdiane.com

The puzzle pattern of this ribbon reflects the complexity of autism, while the colors and shapes represent the diversity of people and families living with this spectrum of disorders. Taken from drdiane.com

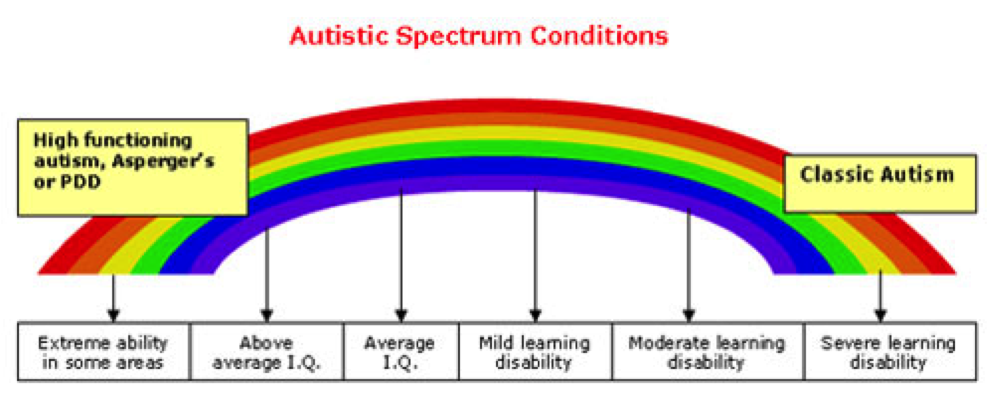

People with autism are classed as having Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and the terms autism and ASD are often used interchangeably. The term “spectrum” refers to the wide range of symptoms, skills, and levels of disability in functioning that can occur in people with ASD, which includes Asperger syndrome. Some children and adults with ASD are fully able to perform all activities of daily living while others require substantial support to perform basic activities. ASD occurs in every racial and ethnic group, and across all socioeconomic levels. However, boys are significantly more likely to develop ASD than girls. The latest analysis from the U. S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 1 in 68 children has ASD.

Taken from myaspergerschild.com

Taken from myaspergerschild.com

According to the CDC, “diagnosing ASD can be difficult, since there is no medical test, like a blood test, to diagnose the disorders. Doctors look at the child’s behavior and development to make a diagnosis.” More details from the CDC are provided at this link.

Notwithstanding this current difficulty for diagnosis of ASD, research has led to continuing progress toward possible blood tests for ASD, which is the focus of this blog and supplements an earlier posting here on treating autism with a broccoli nutraceutical.

ASD and Exome Sequencing

My Google Scholar search for “autism and sequencing” led to a mindboggling list of more than 47,000 items! When ordered by relevance rather than date of publication, two publications were each cited ~1,000-times following “back-to-back” appearance in venerable Nature magazine in 2012. This computes to a combined average of ~400 citations per year, or a fraction more than one citation per day on average, which to me signals significant attention by the ASD research community and thus worth commenting on herein.

Sanders et al., in the first of these two widely cited studies, carried out exome sequencing in 238 families wherein each pair of parents was unaffected by ASD but had a child who was affected (aka proband), and in 200 of these families there was an unaffected sibling. This study design feature is important in view of the widely held idea that complex personality traits are derived by a combination of “nature and nurture,” i.e. genetics inherited from parents and that which is learned or otherwise acquired by familial and all external events.

Before synopsizing what was found, I should note that germline single-base mutations spontaneously arise during mitosis in every generation, and are termed de novo single nucleotide variants (SNVs). Identifying SNVs remained refractory to analysis at the whole genome or exon level until the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies.

Sanders et al. found that the total number of non-synonymous (i.e. changes in the amino acid sequence of proteins) de novo SNVs—particularly highly disruptive nonsense and splice-site de novo mutations—are associated with ASD. They concluded that their results “substantially clarify the genomic architecture of ASD, demonstrate significant association of three genes—SCN2A, KATNAL2 and CHD8—and predict that approximately 25–50 additional ASD-risk genes will be identified as sequencing [more>

families is completed.”

Neale et al., in the second widely cited study, likewise conducted exome sequencing but on only 175 ASD probands and their parents. Nevertheless, they found that the proteins encoded by genes that harbored de novo non-synonymous or nonsense mutations showed a higher degree of connectivity among themselves and with previous ASD genes as indexed by protein-protein interaction screens. They concluded that their results “support polygenic models in which spontaneous coding mutations in any of a large number of genes increases risk by 5- to 20-fold,” but did acknowledge the strong evidence reported by Sanders et al. for individual genes as risk factors.

ASD Genetic-Risk Testing

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in 2013 issued a statement on ethical and policy issues for genetic screening of children for ASD that was prompted in part due to then recent progress by IntegraGen—a small French genomics company—on development of a gene test that uses a cheek swab to screen infants and toddlers for 65 genetic markers associated with autism. Highlights of the AAP’s statement include:

- Genetic screening can be particularly useful for diagnosing older babies and children with developmental disorders such as autism.

- Genetic screening should be made available for all newborns. However, parents should have the right to refuse screening after being informed of the benefits and risks.

- The decision to offer testing or screening should be based primarily on the best interest of the child.

Taken from autismspeaks.org

Taken from autismspeaks.org

By way of an update, I’m pleased to add that in a 2015 press release by IntegraGen it was announced that its ARISk® Test became the first test marketed in the U. S. to assess the risk of autism spectrum disorder in children. Among the following IntegraGen statements about the ARISk® Test, I think it’s most important to note the caveats I’ve bolded for emphasis:

- The test does not confirm or rule out a diagnosis of ASD for the child tested.

- The test is intended to be used together with a clinical evaluation and other developmental screening tools.

- Intended for children with early signs of developmental delay or ASD and in children who have older siblings previously diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder.

- A genetic score, based on the total number of genetic markers associated with autism identified, is used to estimate the child’s risk of developing ASD.

- Intended for use for children 48 months and younger. The ARISk® Test is not available for prenatal testing.

More recently, Courtagen—cofounded by my former Life Technologies colleague Kevin McKernan (coinventor of SOLiD® NGS)—has commercialized its sequencing analyses for ASD and other neurodevelopmental conditions. According to a Courtagen posting, “[i> n the absence of a known single-gene disorder, ASD likely involves a complex combination of both genetic and environmental factors that influence early brain development. Multi-gene panels, such as Courtagen’s

Some interesting—to me—logistical and operational information about devSEEK® (237 genes) is as follows:

- Turn-around time for results is 4-6 weeks.

- DNA for sequencing is extracted from a single saliva sample. No blood draw or muscle biopsy required; however, blood and muscle tissue are accepted.

- Courtagen works with patients, physicians, and insurance carriers to pre-approve each test. Courtagen will bill the insurance company and is willing to handle an appeal process as needed.

- A secure physician online portal is available for ordering genetic tests and accessing patient reports when completed. Genetic counselors are available to address questions regarding Courtagen test results.

ASD Research and TriLink

While mulling over how to conclude this Autism Awareness Month blog featuring genetic testing for ASD, I wondered about TriLink’s role in advancing autism research by virtue of its various nucleic acid-related products being used for autism investigations. I was pleased and proud to find more than 40 items by searching Google Scholar for articles with the words “autism and TriLink.”

Perusal of these items revealed that the most cited (450-times) report was a 2012 publication in highly regarded Cell titled MeCP2 Binds to 5hmC Enriched within Active Genes and Accessible Chromatin in the Nervous System, which used TriLink 5-methyl-2'-deoxycytidine-5'-triphosphate (5m-dCTP). Given the apparent significance of this publication, I won’t try to give a short, simplified synopsis but rather quote the following part of the authors’ summary:

“We report that 5hmC [5-hydroxymethylcytosine> is enriched in active genes and that, surprisingly, strong depletion of 5mC [5-methylcytosine> is observed over these regions. The contribution of these epigenetic marks to gene expression depends critically on cell type. We identify methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) as the major 5hmC-binding protein in the brain and demonstrate that MeCP2 binds 5hmC- and 5mC-containing DNA with similar high affinities. The

I also noted a 2016 Cutting-Edge Review in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology titled A CRISPR Path to Engineering New Genetic Mouse Models. These investigators utilized TriLink Cas9 mRNA for gene editing analogous to that reported by others for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of the autism gene CHD8 (see above). This led to transcriptomic profiling showing that CHD8 regulates multiple genes implicated in ASD pathogenesis and genes associated with brain volume.

In conclusion, I must say that I learned much new information about autism while researching this blog, which I hope you found informative as well as interesting. If so, I have achieved my goal of either increasing or reaffirming your awareness of autism, and the availability of genetic risk-assessment tests.

As usual, your comments here are welcomed.

Postscript

Recently, a team of academic researchers in Arizona made headlines with their publication in Microbiome reporting ties between autism symptoms and the composition and diversity of a person's gut microbes, aka “gut microbiome,” about which I’ve commented on in several previous blogs.

The participants, who were 18 children with ASD (ages 7–16 years), underwent a 10-week treatment program involving antibiotics, a bowel cleanse, and daily fecal microbial transplants over 8 weeks. Remarkably, the new therapy seemed to provide some long-term benefits, including an 80% improvement of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with ASDs and roughly a 20% - 25% improvement in autism behaviors, including improved social skills and better sleep habits.

Click here for a simplified, educational video on this work by the principal investigator, Prof. James B. Adams at Arizona State University.

I should emphasize that this is a very small study, and much more research will be needed to verify and firmly establish possible benefits and risks. Interested readers should contact Prof. Adams regarding any questions they might have.